Calcium is an essential mineral that accounts for 1.5–2 % of total body weight; an average adult therefore carries ≥ 1 200 g. Roughly 99 % is locked in bone and teeth, while 1 % circulates in blood, maintaining a dynamic equilibrium with the skeletal reservoir. Insufficient calcium causes growth retardation, osteoporosis, joint pain and muscular weakness. Modern nutrition holds that calcium should be supplied throughout life, especially for children, the elderly, post-menopausal women—and even stone-formers.

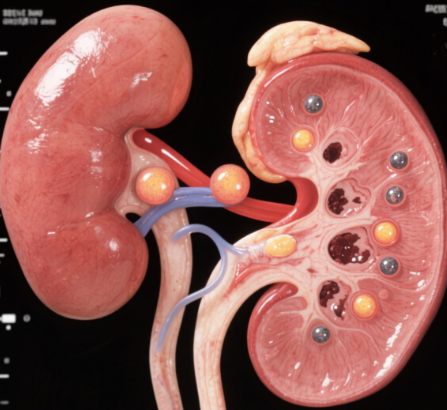

Nephrolithiasis is common after middle age. The traditional view that “high calcium intake begets stones” has been questioned. Ninety percent of renal calculi are calcium oxalate, yet结石 formation is now viewed as the net result of multiple factors: genetics, endocrine status, co-morbidities, obesity, parasites, food preferences and serum calcium. Four principal mechanisms are recognised: supersaturation, inhibitory activity, promotor activity and crystal retention. A large British trial found that subjects with the highest calcium intake had the lowest stone incidence. The real culprit is not dietary calcium but disordered calcium metabolism. When bone calcium is mobilised to blood, vascular smooth muscle contracts, small vessels spasm and “senile” hypertension may follow. In the kidney, oxalate concentration—not calcium load—drives crystallisation. If oxalate is abundant it will bind calcium released from bone and form new stones or enlarge existing ones even when calcium intake is zero. Restriction therefore offers no protection, whereas rational calcium supplementation is safe and necessary; otherwise the elderly lose bone mass and develop more severe osteoporosis.

Dietary calcium is the preferred source. Stone patients are encouraged to eat tofu, milk, yoghurt, small fish eaten with bone, shrimp shells and marine products—foods that supply protein along with easily absorbed, loosely structured calcium that resists crystallisation. Simultaneously, reduce high-oxalate items and exploit anionic competition: drink citrus-based beverages or eat fruit to provide citrate, which competes with oxalate for free calcium and limits insoluble calcium-oxalate deposition.

When dietary measures are insufficient, add a bio-active calcium preparation (pearl calcium, Ju-neng-calcium, Caltrate-D, Shen-yi active calcium powder) plus vitamin D to enhance intestinal uptake. Calcium gluconate and plain calcium carbonate are poorly utilised. The anion of bio-active calcium binds excess cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) in the renal tubule and carries them out as insoluble salts. Absorption also requires phosphorus in a Ca:P ratio of 3:2; milk, eggs, meat, fish and legumes supply phosphorus. A daily intake of 1–1.5 g calcium neither exacerbates stones nor harms kidneys and will improve osteoporosis. Intakes > 2 g may precipitate in the kidney. Alcohol and coffee should be limited during supplementation.

Finally, existing calculi should be removed when indicated, and prevention continued:

- Drink enough water to lower urinary supersaturation and wash out calcium oxalate crystals.

- Avoid or blanch high-oxalate foods (spinach, strawberry, amaranth, water-spinach stem, beet, black tea, chocolate, dried bamboo shoot, pickled vegetables).

- Pharmacological inhibitors—magnesium, potassium citrate, orthophosphate, exogenous acid mucopolysaccharides—further reduce stone recurrence.

| Section | Key Messages (English) |

|---|---|

| Body calcium facts | 1.5–2 % of body wt (≈ 1 200 g); 99 % in bone/teeth, 1 % in blood; deficiency → growth failure, osteoporosis, pain, weakness. |

| Lifelong needs | Children, elderly, post-menopausal women & stone-formers must maintain intake. |

| Old vs new theory | Excess Ca NOT the cause; disordered Ca metabolism mobilises bone Ca → high serum Ca & oxalate still crystallises if urinary oxalate high. |

| Evidence | Large UK study: higher Ca intake → lower stone risk; restriction does NOT prevent stones but promotes osteoporosis. |

| Preferred source | Diet first: tofu, dairy, small fish with bones, shrimp, marine products (high absorption, low crystallisation risk). |

| Anti-oxalate tactics | Limit high-oxalate foods; use citrate (citrus drinks/fruit) to compete with oxalate for Ca. |

| Supplement if needed | Bio-active Ca (pearl Ca, Caltrate-D, etc.) + vitamin D; avoid poor-absorption salts (gluconate, plain carbonate). |

| Ca:P ratio | Maintain 3:2 with phosphorus-rich foods (milk, eggs, meat, fish, legumes). |

| Safe dose | 1–1.5 g/day: improves bone, does NOT worsen stones; > 2 g/day may precipitate in kidney. |

| Lifestyle during Rx | Avoid alcohol & coffee; stay well-hydrated. |

| General prevention | Drink plenty of water; blanch high-oxalate veg; consider inhibitors (Mg, K-citrate, orthophosphate, acid mucopolysaccharides). |